Archive for the ‘Oireachtas’ tag

Seating plan for Dáil Éireann

Update, January 25, 2011: This post has now been superseded by a similar site I’ve built elsewhere, called Who Sits Where?, and which can be found at www.whositswhere.info.

The post below links to the seating as of December 2, 2010, to account for the new seating arrangements on the opposition benches following the election of Pearse Doherty. This arrangement was superseded on January 25, 2011, when the Green Party moved to the opposition benches.

~~

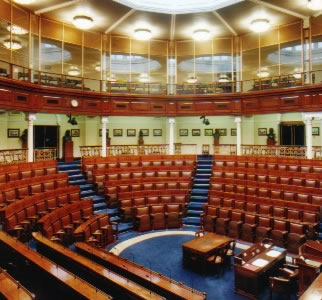

After watching a few electronic votes in the Dáil last week and being a little stumped as to why certain dots in the middle of the opposition half of the chamber were consistently showing up in green and not red, I went looking around for a copy of the Dáil’s seating plan.

I wasn’t able to find one anywhere online so emailed the clerk of the Dáil’s office looking to see if they could help; I got an email back this morning from Gina Long in the Clerk’s office (thanks, Gina) with a copy of the seating plan, and a list of who sits in which seat.

Given the amount of people who were keen to get a hold of a copy of this when I went looking around on Twitter last week I’m throwing up the copy here for public reference. The chart and accompanying lists can be referenced when looking at the electronic voting display on Dáil broadcasts.

The seating plan was supplied in .dwg format so I’m uploading a .jpg copy here for the sake of easy access; the list of seats comes in two formats, one sorted by seat number and the other sorted by each TD’s surname in alphabetical order.

The Upper House rules

A piece I wrote for today’s University Observer on Seanad reform and why getting rid of the Seanad, as per Enda Kenny’s proposal, is a myopic and short-term solution to a longer-term problem…

~~~

Let’s be clear from the off: Seanad Éireann is an imperfect institution. It is little more than a political car park for those postponing the inevitable decline into retirement; a breeding ground for a political party’s new hopes, trying to blood their new meat in the life of Leinster House before the savagery of the Dáil floor; and a consolation prize for those who came close-ish to winning a seat in the lower house in the previous election.

Its work is limited; its relative power to put a stop to legislation is nil; its members largely wish they were elsewhere. It’s a morose place where the good go to die and the young come to roar, all just to get a few minutes’ token coverage on Oireachtas Report three times a week for their trouble.

With the Seanad being the almost entirely useless entity it has become, it was prudent for Enda Kenny to take a stab (almost literally) last week by proposing its abolition, saving the taxpayer about €25m per year, as part of an Oireachtas reform package that would also see the number of TDs cut by about 20 per cent. The country has grown frustrated with a body that it sees as nepotistic and ineffective, and Kenny needed to be seen as proactive in tackling what is, legitimately, a high-profile waste of exchequer money.

With the Seanad being the almost entirely useless entity it has become, it was prudent for Enda Kenny to take a stab (almost literally) last week by proposing its abolition, saving the taxpayer about €25m per year, as part of an Oireachtas reform package that would also see the number of TDs cut by about 20 per cent. The country has grown frustrated with a body that it sees as nepotistic and ineffective, and Kenny needed to be seen as proactive in tackling what is, legitimately, a high-profile waste of exchequer money.

The abolition of a house of parliament is a big choice to make, and one that here, at least, would require a referendum of undoubted painstakingness equal to a Lisbon. Process aside, it’s also a fundamental amendment to the operation of a parliamentary democracy. What Enda Kenny seems to have overlooked, however, is that the Seanad can easily be reformed into a body that works, without necessarily triggering any political seachanges.

The Seanad, in its current form, was established by de Valera’s new Constitution in 1937, with its makeup inspired by Catholic social teaching of the times, led by Pope Pius XI and his visions of social order being based on the co-operation of vocational groups (a system that can be likened to the modern notion of social partnership). With this in mind, the Constitution established five Vocational Panels, with the prevailing logic being that nominees would have special experience or knowledge of one of the five topics, thus becoming eligible for election to that panel. So, for example, those with knowledge or experience in the business world would be elected to the Industrial and Commercial Panel.

The overall aim was that while the directly elected Dáil would remain – as all lower houses are – a political playground, the Seanad would be able to meditate on the nitty-gritty of applying the Dáil’s legislation in the real world, and transcend the relatively lowly bickering of a party political system.

In the seventy-odd intervening years, though, the Seanad hasn’t worked out quite as planned. Because the members of the five Vocational Panels are elected by members of the country’s town and county councils, the elections have become purely party political, with councillors from a political party voting along their own party lines so that the Seanad ultimately mirrors the political constitution of Ireland’s local government.

Another provision allowing for six members to be elected by graduates of Ireland’s two universities (at the time), the University of Dublin – comprised solely of Trinity College – and the National University of Ireland, including UCD, has fallen flat over the course of history. Ireland has seen newer universities formed in the meantime, and despite a referendum allowing the law to be amended to the contrary, the graduates of these colleges have not yet been offered a vote – creating the valid perception that the authority of the Seanad, like its membership, is limited to a minority of society.

While abolition of the Seanad would solve both of these problems, realistically Enda Kenny’s better legacy would be to reform the Seanad in a meaningful way that allows it to best fulfil the intent of the Constitution. An easy start would be to propose the legislation the Constitution already allows for: a law allowing the graduates of other third-level institutions to vote in the university constituencies.

It’s not as if the Seanad hasn’t come up with enough ideas on how to make itself more useful: no fewer than twelve reports on reform have been published over its lifetime. Indeed, only five years ago one of its own subcommittees recommended the abolition of the Panels, opening up nearly half of the seats to direct public elections, and that the eleven seats filled by the Taoiseach’s own appointees be more reflective of the Republic’s role in Northern Ireland, rather than – as present – being merely used to pad out the Government’s majority in the upper house.

The public, however, shouldn’t be surprised if Enda Kenny changes his tune should he somehow manage to lose the next election; he’ll find that due to his party’s victory in the local elections last June, his party will be in the majority in the Seanad irrespective of the nominees of an opposing Taoiseach. In that light, don’t expect the referendum to come any time soon.

But where does it start?

Yeah, I know, I’m actually blogging! Well, now that I can no longer describe myself as a student (a habit I’m going to find it quite difficult to get out of, I fear) and have to label myself as a “Sports Press Officer” – I’ll explain some other time – I’m going to probably have a little bit more time on my hands. I really can’t believe my five years of UCDness are over, but that’s for another day. Also contributing to my general time-having is the fact that we’ve moved house and now live on Upper Leeson St meaning that travelling is a much less cumbersome exercise, particularly when you can walk to most places.

On that theme, last Wednesday new housemate Mulley organised a bloggers’ tour of Leinster House with the Green Party. It had been ten years since I was inside that place (being classmates with ministerial offspring gets you fairly cool CSPE tours, folks) but since my political enlightenment of sorts, it was the first time to really take in the nature of the place. Ciaran Cuffe, our host, was an utter gent, extending the tour to the party’s offices inside Leinster House and to the Dáil Bar where he was more than happy to have proper chats with anyone who wanted them. Thus, myself and Brennan got a few minutes to have a reasonably in-depth chat with him about life as a TD, the challenges of representing an area with disparate social circumstances, and generally about the function – and more pressingly, the functionability – of the legislature itself.

Here I’ll pause for a quick politics lesson for those who might not be so interested. In the classical breakdown of Government, there are three branches of power: the executive (the panel of Ministers/Secretaries – in Irish terms, the Cabinet), who are charged with overseeing operations and issuing orders; the judicial (the courts system) who rule on the validity of laws and punish those who breach them; and finally the legislature (the Oireachtas), whose job it is to actually make those laws.

Last week on The Late Late Show, Pat Kenny decided to warm up for his new Questions-and-Answers-replacing political debate show by hosting a discussion on parliamentary reform (you can watch it here – skip to 1:16.45). Fintan O’Toole argued for the wholescale reconstruction of most of the bodies, and while people can always choose which parts to agree with and which to ignore, the one part that resonated with me was O’Toole’s assertion that in Ireland, we simply don’t have a functioning government as it’s described in the three-branches approach. The judiciary and executive both work – obviously their merit or competence is a matter of personal opinion) – but the legislative branch simply fails to function. In Ireland, the executive introduce a Bill, it is never debated with any substantive result, and the Government will always get what it wants and have the Bill passed. There is no debate; there is no constructive process leading to a concrete suggestion. The legislature don’t even, as a rule, introduce legislation: the executive comes up with something and the legislature rubberstamp it.

So what do you do about this? After the Late Late debate there is clearly a level of public appetite to examine the alternatives to the PR system or our multi-seat constituencies. So when I had the chance, I asked Ciaran how he felt it would start. Does it, I propositioned, start with his Green colleague, John Gormey, using his capacity as Minister for Local Government declaring he wants a reform and merely introducing a Bill? I remembered his predecessor Noel Dempsey doing something similar before the turn of the millennium and getting nowhere. What needs to happen before a Minister can make such moves and that they actually get somewhere? Why can every Fianna Fáil TD on the Late Late say they agree that reform is needed, but not be in a position to implement it?

The problem is that there is no set path. Are our politicians too scared to be the ones seen to destroy our nice cosy overrepresented system? Are TDs too lazy to introduce single-seat constituencies where they don’t have the option to pawn off any work to other reps for the same people? Ciaran, interested as he was, wasn’t really sure of a solution. If you do, I’d love to hear it.

—

The Dáil trip is described in more detail by Mulley, Darragh and Mark. Oh, and because she asked for a shoutout, hello Steph. 😛

Meanwhile, Scally has started his photobloggery over at cdscally.com. Check it.